I never set out to live a straight line. My life bent itself into circles, spirals, loops that doubled back on themselves. Some were mistakes, some were survival, and some—if I’m honest—were the only way I knew to get to the truth.

I’ve been many things: actor, farmer, dreamer, troublemaker, prophet, and fraud—sometimes in the same week. I’ve sat at tables with Hollywood stars and old medicine men on the prairies. I’ve shoveled compost at dawn, sung opera on roller skates, invented thirteen flavors of rice cakes I sold across Europe, and once sold gold and silver I didn’t own over a phone in Los Angeles.

Every one of those scenes is true. But the only through-line that ever mattered was vision—not the kind you read on eye charts, but the kind that comes in dreams. Dreams are unruly. They arrive in images, fragments, half-spoken sentences, and they don’t care about your plans. Sometimes they whisper, sometimes they roar. And if you follow them, they lead you places no mapmaker ever thought to draw.

That’s how I’ve lived—following whispers and thunderclaps. Making a life out of detours. Sometimes finding joy, sometimes landing in a ditch. This isn’t a straight line; it’s a spiral. Not a sermon, but a record of the strange routes that brought me here.

Thanksgiving weekend, Vineland, New Jersey, 1986. The Wild West—buffalo riders, sharpshooters, a gunfight staged around a false-front town. The Fraternal Order of Police sponsored it. I produced it. I starred in it. Clayton Moore—the Lone Ranger himself—showed up. Two thousand seats filled fast. It was theater, circus, ritual—half-scripted, half-chaos. When the lights hit the false-front town, the boards seemed to breathe.

Clayton walked out—mask gone, sunglasses on—and the crowd erupted. To them, he wasn’t an actor. He was The Lone Ranger.

A year later, in Westport, Connecticut—old money, farms, Paul Newman country—I wrote a musical about immortality and true love with my friend Joe Bailey, one of The Muppets writers. We called it The Legend of Appaloosa. It was about a carnival barker who finds the elixir of life, only to give it up for love.

In the American West, legends are made of outlaws and lawmen. Into that world I came: a showman named Appaloosa Andy. The name was given by an old medicine man, Fire Owl. He said the Appaloosa wasn’t the fastest horse—but it was the one that endured. The one that went the distance.

What you’ll find in these pages are the moments that marked me—the people I followed, the visions I chased, the truths I stumbled into, the spirits that tracked me down, and the strange luck that kept me alive long enough to tell on myself.

This isn’t the story of a man who found the path. It’s the story of a man who walked off every path he was given and still managed to arrive somewhere that feels like now.

If there’s a thread through all of it, maybe it’s this: I never stopped believing the world was stranger, wilder, and more possible than the version we were handed. I tried to live inside that possibility, even when it broke me. Especially when it broke me.

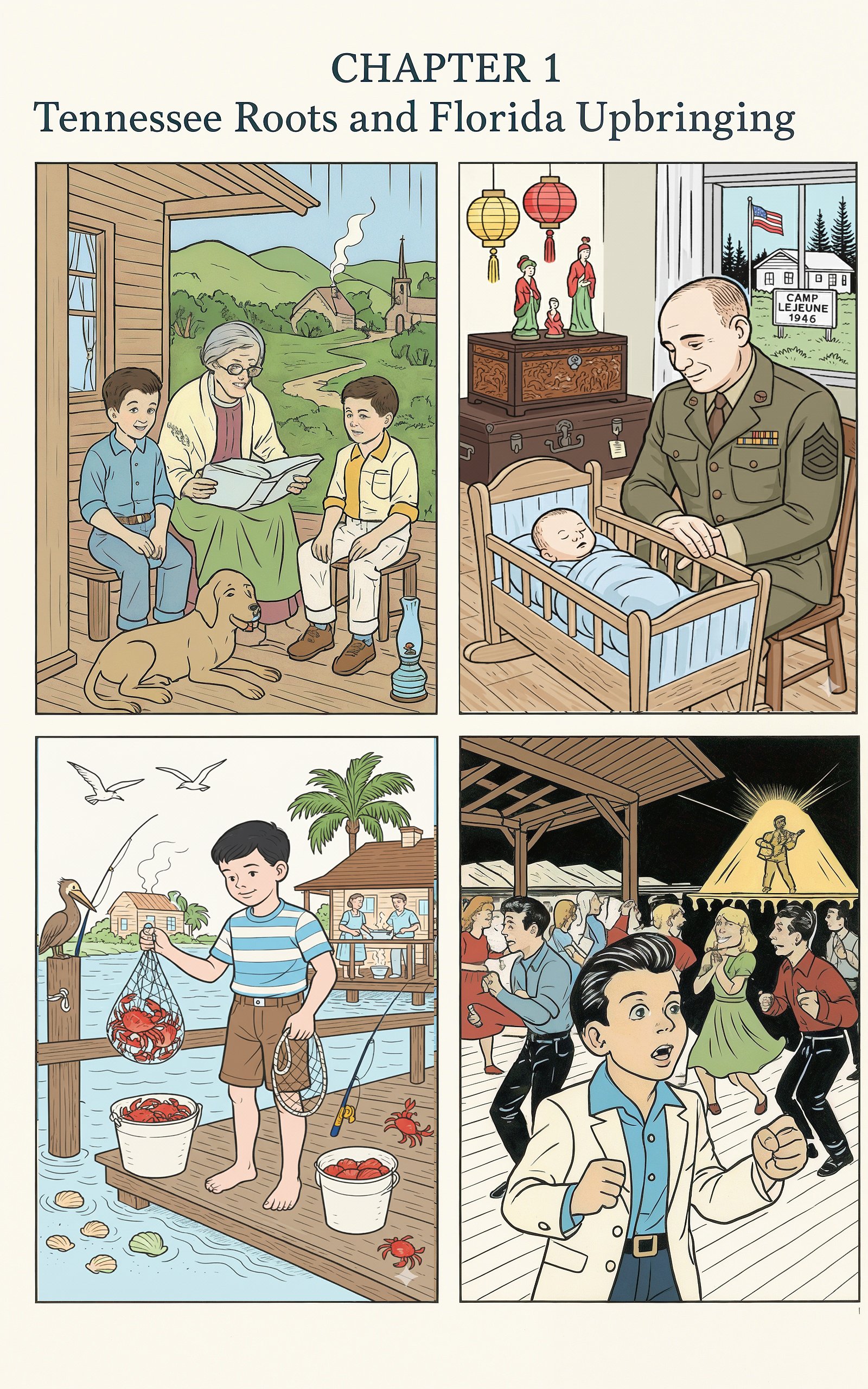

I was born in 1946 at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina. My name carried its full weight — Andrew Jackson Cooksey IV — a name already worn by three men before me. My father, Andrew Jackson Cooksey Sr., was a Sergeant Major in the First Marine Division. He had landed on Guadalcanal, Okinawa, and Iwo Jima. A war hero.

Before that, he had spent six years in China with the Marines. He brought those years home in fragments — the sound of street markets, the red paper lanterns. He also shipped back carved chests, ancient porcelain figurines and dishware. He loaned it to the Tennessee State Museum. They “lost them” and never gave it back. The stories remained as my inheritance.

When I was a year old, we left Camp Lejeune and moved to Tennessee, to the family’s ancestral home on Yellow Creek in Houston County. Our family’s graveyard was close by with the first Andrew Jackson Cooksey buried there. My parents enrolled in college, and my grandmother took charge of me.

My parents were young and still finding their footing, both in school and in life. They were strict in principle but gentle in practice, believing curiosity could teach as much as discipline. My grandmother kept a steady hand on me, but my father balanced her firmness with play. On long drives through the rolling hills, he would speed up just before a rise, and as the car lifted and our stomachs dropped, he’d laugh and shout that we were on a roller coaster. My mother pretended to scold him, but even she was smiling. Those rides taught me that adventure could live in ordinary moments — a lesson that would follow me long after Yellow Creek.

The creek ran across the road from the house, the air thick with honeysuckle, the nights lit by fireflies. In the daytime, we swam in the muddy water, toes curling in the silt, the call of whippoorwills echoing at dusk. My cousin Jakey watched over me in those years. He was older, surer on his feet, and he had a way of keeping me out of the deepest water. He wasn’t much older, but to me he was a giant — someone who knew the creek, the woods, the hidden paths. Jakey was family in the truest sense: rough around the edges, but steady.

Sundays were the still point in that world. Granny’s hands smelled of biscuits and lye soap, and her hymns rose before dawn while the coffee percolated on the stove. The men shaved with straight razors and spoke softly until breakfast was cleared. Then came church—hard wooden pews, the whine of ceiling fans, and the preacher’s voice rising like heat. The women wore cotton dresses that rustled when they stood to sing, and the children fidgeted, waiting for the final amen so we could run outside into the bright Tennessee air. I remember the sound of the creek beyond the church, and how its shimmer seemed to carry the hymns downstream.

My mother was the eleventh of thirteen children, her head filled with plant knowledge and remedies, the kind passed down in a family where women worked the land and kept people alive. My grandfather was a farmer but also a scholar, insisting education was the only way forward. Granny sat every night with her Bible open, reading aloud. My father balanced discipline with lenience. Duty and curiosity braided together in that place. My sister Trudy was born a few years later.

My parents’ drive for education set the rhythm of our family life. Books piled on the kitchen table beside lesson plans and grade books, and the talk around supper was always about students, exams, or the next semester. I grew up believing learning was a kind of service—something you did not just to advance yourself but to pull others forward too. Yet even then, I sensed that my lessons would come less from classrooms and more from the road ahead. While my parents built careers of structure and order, I was already restless for the spaces between, for what couldn’t be graded or planned.

My parents moved us to Gainesville, Florida to finish their graduate degrees in education. We then moved to small towns in northern Florida every year as my mother took teaching positions and my father became the school’s principal.

Each new town felt like a fresh start and an interruption all at once. We’d unpack boxes, learn new streets, and I’d figure out where I fit in just as we were getting ready to move again. The schoolyards changed, but the rhythm stayed the same — new faces, new teachers, and the quiet understanding that nothing lasted long. Those constant moves taught me to adapt quickly, to read people, to become whoever I needed to be. Without realizing it, I was already rehearsing the art of transformation that would define so much of my later life.

When I was nine, we moved to Panama City, Florida. St. Andrews Bay, right in front of our house, was still unpolluted then. I could net blue crabs right off the pier, wade waist-deep and feel scallops brushing against my toes. I would head out at dawn with buckets and come back heavy with the day’s catch. At night, we ate what we pulled from the sea — steamed crabs and pan-fried scallops that tasted like salt and sunshine.

It was in Panama City that I discovered Elvis and rock ’n’ roll. I was nine years old, dressed like him in hand-me-downs cut to fit the style. My sister Trudy and I sang Everly Brothers harmonies together. For me, the music was freedom, rebellion in a voice that shook the walls. I wasn’t just watching Elvis; I was trying to be him. My older cousin from Tennessee, who stayed with us some summers, would sneak me into shows in Panama City Beach. I lived for the lights, the screams of teenage girls. I was only nine, but I felt sixteen. The concerts were noise and possibility — a door cracked open onto another world.

The sweat, the teenage girls’ cheap perfume, the boys’ Old Spice cologne, the stomp of feet on wooden floors — it was intoxicating. I wasn’t just watching; I was becoming Elvis. I imitated his moves, his swagger, and grew my hair long. At home I practiced in the mirror until my body found its own rhythm.

Those nights at the beach pavilions, Buddy Holly’s glasses would catch the light, the Everly Brothers’ voices would blend until they seemed like one sound. I stood in the crowd trying to see over their heads, but I felt taller than all of them. It was electricity. It was music that made me want to be someone and somewhere else.

I didn’t know it then, but those nights under the pavilion lights were rehearsals for the rest of my life — chasing the next stage, the next song, the next horizon.

The horizon, as it turned out, was not a line but a promise—one that kept shifting every time I thought I’d reached it. Florida’s salt air had given me a taste of motion, and I began to see the world as a stage waiting beyond the Gulf. I didn’t yet know its name—New York, Hollywood, the high plains of South Dakota—but I could feel it calling, the same way the music had: loud, electric, impossible to ignore.

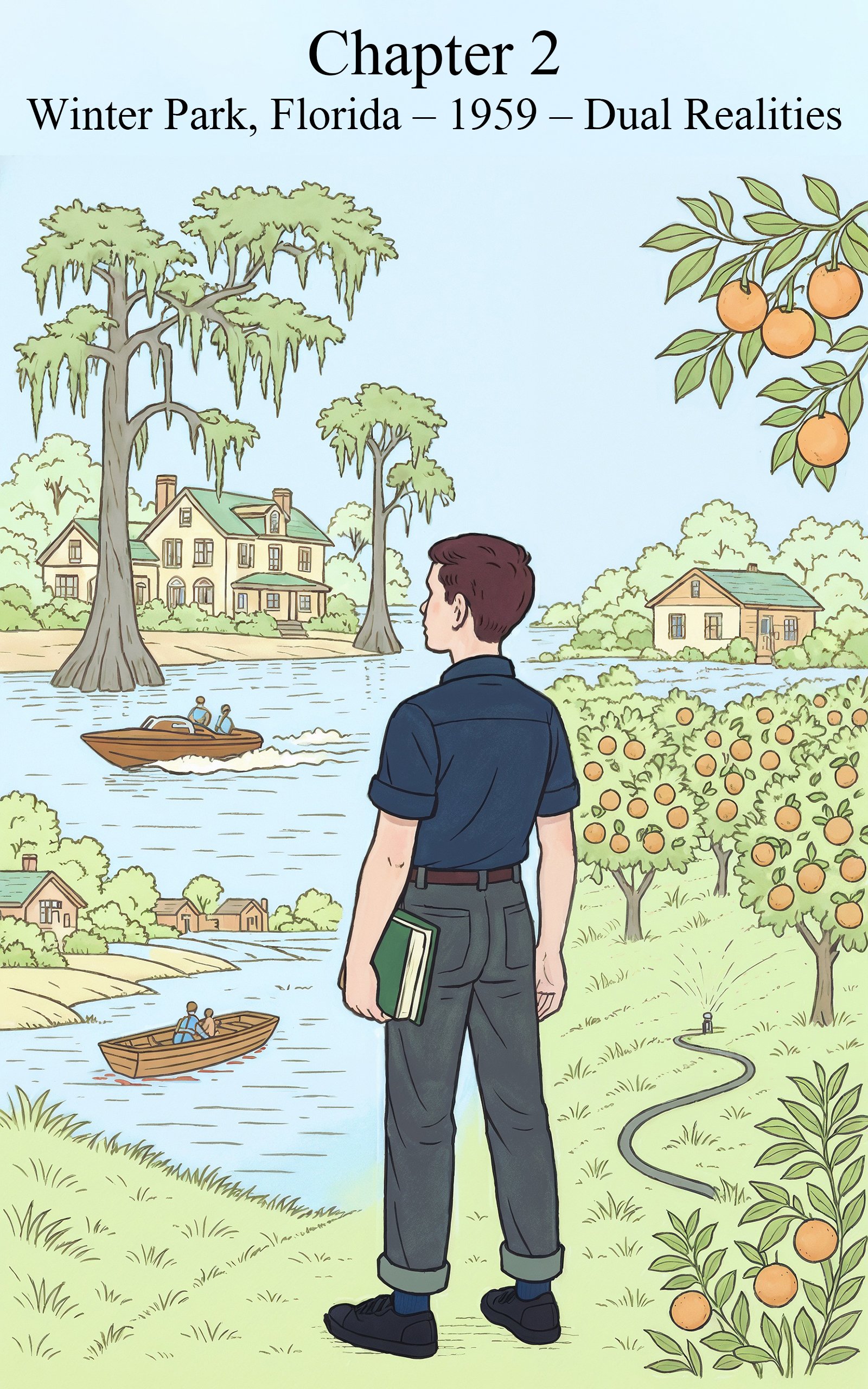

This chapter captures my adolescence as a balancing act between appearance and authenticity — the tension between the orange-grove suburbs and the polished world of privilege. It traces my initiation into performance, spirituality, and desire: learning to “pass,” reading the red letters of Scripture to my grandmother, and testing love’s boundaries with Susie before being sent to Forest Lake Academy — where a new friendship with Ricky begins to reawaken my sense of freedom.

After Panama City, the tides of childhood freedom gave way to something quieter, more contained. My father had taken a new position in Winter Park, and with it came a different kind of schooling — not just in classrooms, but in how to move through worlds that didn’t see each other.

After Panama City, we moved again, this time to Winter Park. The town had two faces. One belonged to the canals lined with moss-draped cypress and grand lake houses whose screened porches opened onto the water. Ski boats traced lazy figure eights across the connected lakes where old money lived, their wakes rolling toward manicured lawns that smelled faintly of jasmine and cut grass. The other face was ours — the modest subdivision carved out of the orange groves, where the air was thick with fertilizer and the hum of cicadas. The nights carried the scent of blossoms, the steady hiss of sprinklers turning rhythmically over clipped lawns, and the soft rustle of palmetto fronds against the windows.

At school, I met kids whose families belonged to the country club, who vacationed in Europe and wore shoes I couldn’t afford. One classmate, Warren, invited me to his birthday party on the lake. The water was clear, the docks polished, and their house seemed to float between glass and light. I remember realizing that if I was going to belong anywhere, I had to learn how to shift — how to fit. I didn’t see it as deceit then, just survival.

I played the part expected of me — jock by day, little league baseball and football. But inside I was still Elvis, still chasing the freedom of music and the stage. I passed between those two worlds seamlessly, never entirely belonging to either. Winter Park taught me how to pass. How to smile for the principal, shake hands with the minister at church, and then sneak out into the orange groves to daydream other places and other worlds. It was a mindset I’d carry the rest of my life.

Sometimes at practice, while the coach shouted signals, I’d hum rock tunes under my breath. Between innings, I’d imagine the crowd cheering for a concert instead of a ballgame. The Elvis in me and the boy in the uniform shared the same skin — one hidden, one performing. It was confusing, but it made me aware of the masks people wear, the small performances that keep life running smoothly.

My grandmother came to live with us in Winter Park. Her sight was nearly gone. Cataracts clouded her eyes, the world slipping away from her one shadow at a time. But she had her Bible. Every evening she sat with it open on her lap, the worn leather soft from decades of handling. The room smelled faintly of Vicks vapor rub and the liniment she used. The floor fan hummed as the lamp cast her Bible in golden light.

I would read to her because she was almost blind. She would say, “Read the red.” That’s what Jesus said. I read aloud, stumbling at first, then falling into the rhythm of the King James cadences. Jesus overturning tables in the temple. Jesus forgiving the prostitute. Forgive seventy times seven. Her voice cracked but it carried authority, guiding me through the words.

Sometimes, when the verses ended, we didn’t close the book. We talked. She told me about the prophets — Jeremiah, Isaiah, men who wrestled with God, who asked questions and weren’t struck down for asking. I didn’t understand the words then, but I felt as if faith was something you could lean against. I wanted to speak to God directly, without the preacher, without the church. To skip the middleman. To cut through the ceremony and hear a voice answer back in the dark.

Those nights planted something in me. Not certainty, but hunger.

Then there was Susie, my babysitter when I was twelve. By the time I was fifteen she was eighteen, already in college, and I was still just a boy trying to be older than I was. It wasn’t supposed to happen, but it did. She liked the way I knew her, and I liked the way she made me feel wanted. For a while, that was enough. It wasn’t shameful to us. It felt like love, or at least the closest thing I’d known to it.

Her father was a cop, but he never threatened me. He liked me well enough, though the whole thing embarrassed him. What unsettled my family wasn’t scandal or danger — it was that I was moving too fast, pushing past my years, testing boundaries everywhere I could. Still throwing myself at things I didn’t yet understand.

Sometimes after leaving her house, I’d look at myself in the bathroom mirror — crew cut, heartbeat still pounding — and wonder who that person was looking back. I didn’t feel guilty, just aware that I was crossing lines that couldn’t be uncrossed.

When my parents found out, they weren’t furious so much as concerned. Concerned that I was running too far ahead of myself, that I would fall hard. Their answer was to send me away — to somewhere that might slow me down, give me structure. That place was Forest Lake Academy, a Seventh-day Adventist boarding school. It was meant to straighten me out, to box in my wildness with Scripture, rules, and veggie burgers.

The first night there, the dorm smelled of Lysol and starch. They spoke of prophecy and end times that had its own kind of rhythm — and it was there that I met Ricardo Vásquez. Ricky.

I didn’t know it then, but Ricky would open another door — freedom of a different kind.

This chapter captures the summer I left the safety of home behind and sailed to Ecuador on a banana boat at fifteen, chasing freedom with my friend Ricky. In Guayaquil, I fell in love for the first time—with the city, with Muñequita, and with the feeling that the world was finally mine to lose.

He was from Guayaquil, Ecuador. Another boy who was sent away for being too wild. We were roommates and instant brothers. He was dark-eyed, fast-talking, and full of schemes.

At night we’d wait until the dorm fell quiet, the low hum of ceiling fans covering our whispers. Ricky would pull out his contraband transistor radio, the size of a soap bar, wrapped in a sock to muffle the sound. He’d tune to a faint Latin station out of Miami, and suddenly the room filled with forbidden rhythm — bolero, cumbia, laughter in another language. We’d lie there in the dark, the glow of the dial painting his face in pale green.

Once a monitor caught us and yanked the plug from the wall, shouting about “heathen noise.” Ricky only grinned, a cigarette tucked behind his ear. Later, when the footsteps faded, he struck a match, lit up, and blew a ring of smoke toward the ceiling.

I think that’s when I knew we were the same kind of restless — two boys pretending to be tame, already dreaming of the escape route.

At night we whispered about the world beyond school walls. Ricky told me about his city, a seaport alive with music and markets and banana boats. He painted Guayaquil in colors Florida never had. One night he said, “Why don’t you come back with me this summer?”

He meant it. He arranged it with an older friend who worked on the banana ships. Passage for me, free.

I packed my bag, slipped Granny’s red-letter Bible inside, and took a bus to Galveston, Texas, the last port of call. At the dock I boarded the Ballenita, a Norwegian banana boat under contract to United Fruit. Nobody asked why a fifteen-year-old boy was climbing aboard a cargo ship. Nobody stopped me. That was the irony — fifteen and freer than most men ever get to be.

The dock at Galveston had smelled of diesel and salt, the air thick with the cries of gulls. Men shouted in half a dozen languages, loading crates and cables in the dim yellow light.

The Ballenita’s hull rose like a black wall, streaked with rust and promise. I stood there gripping my small suitcase, Granny’s Bible pressed against my chest. Before I left, she’d placed her hand on my head and prayed in her soft Tennessee drawl, asking the Lord to keep me safe “wherever His winds may blow.” The memory followed me up the gangway.

A sailor with hands like rope knots squinted at me and muttered, “The sea doesn’t love anyone, kid. Remember that.” Then he turned and disappeared into the hold. When the ship’s horn bellowed and the dock began to slide away, I felt something break loose inside me — fear, maybe, or the weight of everything I was leaving behind.

The Ballenita was stacked with cardboard cartons, waxed so they wouldn’t collapse in the damp air. They lined the refrigerated holds, fans blowing night and day to keep the green fruit steady — fifty-five degrees below deck, cold enough to keep the bananas from ripening on the voyage.

The smell seeped upward — sweet, grassy, sour. It clung to your clothes and stayed in your mouth. The crew cursed it. To me it was the smell of escape.

Days fell into rhythm — the metallic clang of the galley bell, the scrape of mops on deck, the sing-song curses of men from Oslo and Bergen. I learned to keep out of the way, though not always fast enough. Once I slipped on wet planking and caught the edge of a sailor’s temper. “You trying to get yourself killed, boy?” he barked, shoving a mop in my hand. I learned fast.

At night I’d sit on an overturned crate by the rail, watching the horizon blur into nothing. The moonlight made the sea look like glass, and the slow hum of the refrigeration fans below deck became my lullaby. Sometimes I’d catch the faint smell of bananas and diesel together — sweet and bitter, like freedom itself.

That first night at sea, I cried into my pillow. Quiet, so no one would hear. I cried because I knew the cloak was gone — my parents, my grandmother, all their protection left on the dock. I was on my own. I had to dig down into my dreams, into my visions, into what Granny had taught me. If I didn’t, I knew I was lost.

By morning I walked the deck. Salt spray on my face. Sailors smoked, passed bottles, cursed at the sea. The galley fed us well. Norwegian stews thick with fish and potatoes. Dark bread with butter. Coffee strong enough to burn a hole in the hull. The cook folded in Ecuador: rice and beans, fried plantains, fish soup bright with lime.

I leaned against the rail and thought: This is what freedom tastes like — salt, diesel, and fear.

When we finally came into the Guayas River, the air hit me like a wave. Heavy. Salty. Alive. The harbor was lit with banana boats, little launches darting between them loaded with fruit, sailors, girls, radios blaring cumbia.

Ricky was waiting. He had a little gold Citroën, low to the ground, engine buzzing like a hornet. He hugged me, tossed my bags in the back. “Let the party commence, gringito.”

We tore through Guayaquil. The air was thick and wet, the kind you could drink. Radios blasted cumbia and merengue from open windows. Buses rattled, horns blared, vendors shouted from the curbs. The city didn’t walk — it rocked and rolled to a Latin beat.

We stayed out until dawn. Cafés with ceiling fans that barely stirred the heat. Streets where sailors drank with girls and musicians played until their fingers bled. Ricky knew them all. We drank big bottles of Pilsner, the beer sweating in our hands, and laughed like pirates.

One night we stumbled into a street carnival that seemed to have materialized out of nowhere — drums pounding, torches throwing wild shadows on the walls. Men in devil masks leapt and spun while women in bright skirts twirled until the air shimmered with color. Ricky grabbed a bottle from a passing vendor and poured it into two tin cups. “Welcome to Guayaquil, hermano,” he shouted over the music.

We danced until the sweat ran down our backs, the air thick with sugarcane smoke and perfume. In Florida, midnight meant danger; here it meant the world was just getting started. For the first time, I felt what it meant to belong nowhere — and to love it.

One night Ricky introduced me to Muñequita. Little Doll. She had dark eyes that watched you like you already knew the punchline. An enigmatic smile, quick and slow at the same time. She moved shyly through a crowd as if she owned it, slipping between arms and chairs with a grace that made the rest of the night blur around her.

When she laughed, I forgot where I was. When she kissed me, the room disappeared.

We walked along the harbor, lights flickering on the water. We kissed under ceiling fans that only moved the heat around. For the entire summer we slipped in and out of each other’s arms, the city humming in the background.

We spent long afternoons on the rooftop of her cousin’s house, a tangle of laundry lines and tin roofs glinting in the sun. She’d press her stomach against mine to teach me the cumbia, whispering, “Feel it, not count it.”

Her laughter came from deep inside, full of mischief and music. I taught her a few English words — “crazy,” “kiss,” “maybe” — and she used them like charms, each one a promise.

Sometimes we’d steal mangos from a backyard tree and eat them barefoot, juice running down our arms. Cicadas sang in the heat, ceiling fans turned lazily above us, and the afternoons stretched forever. I knew I was still a boy, but in her arms I felt like I’d already lived a lifetime.

The summer flew. Trips to Salinas on the coast, where the air was sharp with salt and the ocean beat itself against the sand. Nights of dancing the cumbia until my legs shook, Muñequita pressing her stomach to mine to teach me the rhythm. Days of heat, music, beer, and her hand in mine.

Florida felt far away. Boys back home were sneaking beers behind gas stations. I was riding in a gold sports car, drinking Pilsner, kissing a girl who looked like she had stepped out of a magazine.

I told myself I wouldn’t go back. Couldn’t. Ecuador was mine now. My spirit thrived on its rhythm and timelessness.

When the summer ended, Ricky’s family called in favors. There was no American school in Guayaquil, so they reached out to Quito. Ex-president Galo Plaza had founded Colegio Americano there. They got me admitted.

But before I left, Muñequita and I met one last time on the Malecón. The river was black, the city lights dancing on its surface.

We didn’t make promises. We didn’t pretend.

She reached into her bag and pulled out a small silver medallion, worn smooth at the edges. “For the road,” she said, fastening it around my wrist. “So you don’t forget where your heart began.” I didn’t realize then how often I’d touch it in the years to come — a token of a place that had burned itself into me. I would spend years chasing that same kind of heat, never finding it again.

She held my hand. “It was good, wasn’t it?”

“It was,” I said.

We kissed once more. Not like the first time, but softer. We both knew it was over. A summer, a song, already fading as the night closed in. Bittersweet. No regrets.

When the bus climbed toward the highlands, the air cooled and thinned. The coast disappeared behind a veil of mist, and I felt the world tilt from sea level to sky. The boy who had danced the cumbia on the docks was gone; another one was taking his place.

Chapter 4 captures my coming-of-age in the high thin air of Quito—how an adopted family, a city alive with festivals, and a new sense of belonging opened my world beyond the small borders I’d known. It traces how friendship, theater, and the spirit of the Andes ignited in me the certainty that I was meant to live as an artist.

■

Quito sat high in the Andes, a city of sharp mornings where your breath hung in front of you like smoke. Volcanoes ringed the valley, their peaks white with snow, their sides cut with green terraces. The air was thin, almost metallic, and it forced itself into your lungs whether you wanted it or not. I had never lived so close to the sky.

I climbed the mountain behind the city, the Pichincha, one weekend with a small group of classmates, the mountain rising like a gray wall above the city. The climb started in sunlight but ended in cloud, the air so thin it whistled when I breathed. My heart hammered as if trying to break out of my chest, and the wind tasted like metal.

When we reached the ridge, the world fell away in every direction—fields, rooftops, clouds layered like torn paper. I felt both small and invincible, as if the mountain had stripped me down and rebuilt me from air and light.

I lived with an Ecuadorian family—actually a Russian expat who owned a coffee-processing plant. At first I stayed with them while my parents were abroad.

The school was a compound of low white buildings, sunlight spilling through arched courtyards and echoing with a dozen accents—Texas drawls, clipped British tones, Spanish laughter. The flagpole clanked in the wind, and the classrooms smelled of chalk and eucalyptus polish. I kept to myself those first weeks, wondering why belonging always seemed to happen somewhere else.

Mike Hester, my best friend at school, started taking me home, and finally his mother said, “You might as well stay.” His father was the American Air Force attaché, a Texan, and his Puerto Rican wife ran the house with music and rhythm. They had eight children.

The house was loud in the good way—pots clanging, doors slamming, shoes everywhere. Dinner was often rice and beans, chicken pulled from a pot, fried plantains sweet and hot. The colonel said grace like he was giving a briefing. His wife ran the table like a conductor. They folded me into the noise as if I had always belonged. It was the first time I’d felt part of a family that wasn’t my own, and the music of the Andes—especially the rondador flute drifting through open windows—seemed to fill whatever silence I’d been carrying since childhood.

The kids treated me like a cousin. I learned to pass plates, clear dishes, and catch a baby on the fly when a sister shouted, “¡Cuidado!”

The kids at school were different too. Children of diplomats, military attachés, businessmen, Peace Corps directors—a colony of the United States tucked into the Andes. We went to school with the children of the Ecuadorian elite, kids who arrived in polished cars with chauffeurs, wearing crisp uniforms. Between classes we smoked cigarettes and traded stories from home, each of us a little bit foreign no matter how long we’d been there.

We were loud. Restless. Boys in crew cuts and jeans. Girls in skirts smuggled from Miami, bought in shops that catered to the “ricos.” We talked about American football games we’d never play, TV shows we missed, cars we wouldn’t drive for years. We smoked behind walls, tried to act older, and failed most of the time.

The Japanese ambassador’s son was in our class. Quiet, polite, polished shoes and pressed shirts. He had something none of us had: a chauffeur and a black limousine that gleamed like a mirror.

During Carnival he invited a handful of us to pile in. Buckets of water balloons stacked at our feet, dripping cold against our ankles. The chauffeur glanced back in the mirror. “Señores,” he said dryly, “try not to kill anyone.”

We rolled through the streets with windows down. Crowds armed with buckets and balloons of their own. I leaned out, picked my target, and let one fly. It burst across a man’s chest. He shouted, laughed, and shook his fist.

Another balloon. Another scream. Girls shrieked. Boys cursed. Then someone yelled, “¡A los gringos!” and the crowd turned on us. Buckets tipped. Balloons splattered. The limousine was streaked with water, the air full of laughter and shouts. The chauffeur gunned the engine, just enough to keep it fun. By the end we were soaked, clothes dripping, hair plastered to our foreheads. The leather seats squeaked under us. The chauffeur passed back towels like a weary uncle. For that afternoon, we weren’t outsiders or expats. We were kings of the street, drunk on our own laughter.

Once I traveled north to Otavalo. The town square filled with Indian vendors laying out their crafts—woven blankets, ponchos, carved flutes, silver jewelry. They wore their hair in braids, their eyes steady, their hands quick. Their dignity was a presence, not something you could miss.

I bought a small statue of the Virgin as Pachamama, Mother Earth, with what little money I had. It sat on the shelf in my room at the colonel’s house—half Catholic, half earth mother—as if the two faiths had decided to share custody.

It was in Otavalo that I first felt the difference in how the world could be seen. To the Otavaleños, the earth was alive. Mountains had spirits. Rivers had memory. Life wasn’t about conquering nature—it was about living with it, listening to it. That vision stayed with me, even when I returned to the noise of the school and the pull of the city. It also challenged everything I’d been taught about God. I began to imagine the divine as both father and mother, sky and soil, giver and receiver. Pachamama changed my sense of holiness—suddenly, God could be woman, creation itself a form of love that never stopped giving.

Theater found me. A ragtag troupe of expats called the Pichincha Players rehearsed in borrowed halls under bare bulbs. The paint was always still drying on the sets, the costumes stitched together from whatever fabric could be found. I joined them, and the work lit me up. Lines echoing off the walls, the smell of dust and sweat, the nervous energy of waiting backstage. Even in the chaos, it felt like home.

One night, during a rehearsal, I missed my cue entirely. The others froze, the room silent. Then one girl ad-libbed a line that sent the cast into helpless laughter. We stumbled through the scene, gasping for air, and when it ended we all cheered. It was imperfect, alive, and for the first time I understood that the stage wasn’t about pretending—it was about being completely present.

Then the Old Vic came through on tour, performing The Merchant of Venice. Their voices rolled over the Andes like thunder. They filled the theater, shook its rafters, carved Shakespeare into something raw and alive. I sat in the dark and knew: I wasn’t going to become an actor. I already was one.

Quito was cold, but the fire had caught in me. It burned through the thin air, through the nights of wandering the plazas, through the mornings when the mountains glowed pink with sunrise. I had found my tribe. That spark would carry me to stages I hadn’t yet imagined—to the Old Globe, to New York, and far beyond the Andes.

When I returned to the United States, the wide skies of Ecuador still clung to me. The world was tilting toward Vietnam, and my father’s quiet warnings carried the weight of battlefields he’d already survived.

Florida felt flat and small after the Andes. The plazas of Quito, the markets of Otavalo, the humid nights in Guayaquil—they stayed in my bones, and Winter Park seemed like a place I’d lived in another lifetime.

It was the early 1960s, and Vietnam was already casting its shadow. The draft board loomed like a thunderhead. I thought about following my father into the Marines. He stopped me.

Morning light filtered through the kitchen blinds, catching the steam from his coffee. My father sat at the table in his undershirt, the newspaper folded beside his plate. His hands—scarred, steady, sun-darkened—tapped the mug with that same quiet discipline he once used to keep his men alive.

“If you join,” he said softly, “join the Air Force. At least you’ve got a chance of not getting killed. It’s the only branch where the officers are the ones mostly in combat. This Vietnam business is going to get bad.”

He didn’t look at me when he said it. His eyes were somewhere far away—probably Guadalcanal, the steaming jungle and coral beaches that marked him forever. He’d once told me about the night his platoon was ambushed there. A boy from Indiana had died calling for his mother while tracer fire split the darkness. My father’s voice always went flat when he told that story, as if sound itself had gone silent.

He was right. He’d seen enough to know.

By 1963, Vietnam was no longer a distant headline—it was a fuse already lit. The United States had more than 16,000 “advisers” on the ground, soldiers in everything but name. Helicopters thudded over rice paddies. Villages were caught between the Viet Cong in the shadows and the South Vietnamese Army stumbling to hold the line.

American officials spoke in careful language—“counterinsurgency,” “nation building,” “strategic hamlets”—but the war had already slipped beyond pretending.

The world watched in shock when Thich Quang Duc sat in a Saigon intersection, drenched himself in gasoline, and burned without making a sound. What followed wasn’t resolution. It was unraveling.

The recruiter promised me language school. “Chinese,” he said brightly, like a salesman offering a discount. “Bright kid like you? You’ll end up in intelligence. Maybe overseas. Serve your country and learn something useful.”

I nodded, pretending to believe him. My father’s warning echoed in the back of my mind—the Air Force at least gives you a chance.

I signed the papers believing that was where I was headed.

They sent me to medic school instead. Then dental-technician school.

So I ended up at George Air Force Base in California—Victorville. A desert town strung along Route 66, the Mojave wind blowing grit across neon signs and motel parking lots. At dawn, the sky turned copper and pale gold, and the jets cracked the silence wide open.

The hospital smelled of bleach, metal, and the faint sweetness of ether. Rows of dental chairs lined the clinic like interrogation seats. Airmen filed through with chipped molars, bad breath, and the thousand-yard stare of men already counting the days until discharge.

One sergeant, Holbrook, used to sneak cigarettes behind the X-ray room. “Hell of a way to serve your country,” he’d say, exhaling toward the ceiling.

By day, I worked on teeth. I hated it—the antiseptic smell, the whine of the drill, the clamp of metal on gums. My hands in strangers’ mouths. Dental phobia carved into me for life.

But at night, I slipped away to Victor Valley College. I studied acting. I took the stage in student productions. I said the lines like they had been waiting for me all along.

My first role was Nathan Detroit in Guys and Dolls. The sets were wobbly, the costumes borrowed, the orchestra half-drunk—but the magic was real. When the curtain rose, the audience vanished into that pulsing stillness between breath and sound. For the first time since Ecuador, I felt exactly where I belonged.

The balance was absurd: airman by day, polishing fillings and fitting crowns; actor by night, speaking Shakespeare under hot stage lights.

The two lives bled together. Even in uniform, even with war gathering on the horizon, I carried Shylock’s words in my head and the music of Guayaquil in my blood. What the Air Force really had was an actor who could recite soliloquies while cleaning your teeth.

I became close friends with the base commander’s daughter, Sally. Nothing romantic. She studied drama, and her father, Colonel Trimble, came to our performances.

Sometimes Sally and I rehearsed late, sitting on the hood of her car in the desert after the theater went dark. We’d read lines under the stars, scripts fluttering in the wind. She laughed at my exaggerated accents; I teased her about her stage fright. Out there, surrounded by sand and silence, the military world felt far away.

After one show, the Colonel saw us standing together in the aisle. His cap was in his hand. “Good work,” he said simply. Back on base, whenever I saluted him, he’d pat me on the back—a private joke, a quiet acknowledgment. He saw something the Air Force didn’t.

I auditioned for the Old Globe in San Diego. They took me as an apprentice. It was a long shot—I still had two years left in the service—but I went anyway.

The theater felt like a cathedral. The smell of sawdust and velvet. The echo of footsteps. My palms sweated as I launched into Mercutio’s “Queen Mab” speech. The words lifted me, carried me past fear.

When I finished, the room fell silent. Then a voice from the back said, “Good one.”

Will Geer. He nodded slightly, as if to say: You’re one of us.

They accepted me. Just like that. A door opening.

Back at George, I kept the letter in my pocket like contraband. Proof I didn’t belong in a dental clinic. Proof I belonged under the lights.

Then I was summoned to the base commander’s office. Colonel Trimble.

Lowly airmen don’t get called to the commander unless something is wrong. I walked in stiff, saluted.

“Sit down, Andy,” he said.

He studied me, then smiled. “You know, I’m a pilot. A damn good one. You’re an airman—not a very good one. But you’re an actor. A really good one.”

He slid the discharge papers across the desk. “I’m giving you an honorable discharge and an early out so you can go to San Diego. Good luck, son.”

I stared at him. I’d like to claim I saw it coming, but I didn’t. Only the base commander could have done it.

Outside, the desert wind caught the edges of the papers and nearly tore them from my hands. I stood there, watching a jet climb into the sky. Its roar softened to silence, and I realized I was free.

Some parts of your life should remain unseen. Mystery is important. It’s what keeps us alive.

Balboa Park was my new cathedral, and the Old Globe its altar. The summer heat, the smell of wood and paint, and the echo of Shakespeare’s lines fused with the pulse of a country on the edge of war and change. Inside, we conjured spirits and love stories; outside, the world was marching toward revolution. Between Will Geer’s garden, Jon Voight’s intensity, and the laughter that filled those humid California nights, I found what theater truly was—a calling, a ritual, and a rebellion.

The Old Globe looked like Shakespeare’s stage dropped into California—half-timbered and whitewashed, tucked into Balboa Park’s greenery. Wood, paint, and the heat of summer nights curled in the air as if every board had a story to tell.

That season we were doing Romeo and Juliet, The Tempest, Two Gentlemen of Verona. Romeo and Juliet starred Jon Voight as the prince of broken hearts and Lauri Peters as his Juliet. They had recently divorced, so watching them have to fall in love and then die together in the play was powerful.

Will Geer played Prospero in The Tempest, magic in his voice, a shaman conjuring storms. Jon Voight, at six-foot-two, was unusually cast as Ariel, but a powerful presence under Will’s magic. Onstage, they summoned spirits and dreams. I wasn’t sure where illusion ended and reality began for me—it was all magic. The play was alive with spirits like the ones I had seen since childhood. I felt right at home.

I had small parts—servant, messenger, background spirit—but I learned by leaning back in the shadows.

Older actors like Jonathan Frid, who played Caliban and Montague, moved as if they were wearing robes of kings. That discipline felt different from what was expected of me in the Air Force. The stakes here were the power of spoken words, shared emotions, and reality shifting. Miss a cue, and the entire world onstage crumbled.

The other young apprentices at the Globe were already starting the look of the Sixties—long hair, denim, an unspoken thing: hippies in the making. Kiel Martin, Victor Eschbach, Cleavon Little, and others who went on to success in the ’70s started at the Globe. Victor was cast as Tybalt, quietly menacing. Every performance he sparked with something nuanced and dangerous. I envied his fire, the way he carried himself like heat radiating off him.

And when Will’s Prospero spoke of spirits summoned from the deep, a voice in me whispered: not just as actor, but as a conjurer of other worlds. Actor as shaman.

San Diego was a Navy town. Marines in uniform filled the bars, fighter jets screamed across the sky, and the Vietnam War machine rolled forward with the efficiency of an assembly line. Balboa Park at night felt like the world holding its breath. The air stayed warm long after the sun went down, carrying the smell of eucalyptus, dust, and orange blossoms. The Old Globe’s lights glowed like a lantern in the trees, and on performance nights the whole park seemed to lean in and listen. Couples strolled the pathways, shadows moving across the tiled fountains and stucco walls. You could hear the distant thud of drums from a rehearsal space, laughter from the Prado, and the murmur of actors running lines under their breath as they walked from the parking lot to the theater.

After the shows, we spilled out into the night like sparks shaken from a log. Some of us lingered on the steps of the Globe, feet propped on railings, still half in costume, unwilling to let the magic drain off too quickly. Others wandered across the lawn and down toward the reflecting pool, where the koi stirred the water in slow circles under the moonlight. Someone always had a bottle, someone always had a joint, and the conversations drifted from Shakespeare to the draft, from love to mysticism, from rebellion to art, all of it spoken like prayer and prophecy. The world felt bigger than our bodies, and the night had room for every version of who we were becoming.

Driving home through the canyons, the radio played surf rock and early psychedelia. Headlights caught the dust in the air and the silhouettes of palms bending in the breeze. San Diego was still a military town, uniforms everywhere, war humming below the surface. But in Balboa Park, under the Tudor beams and summer sky, we were something else—adventurers, misfits, believers in a world that could be rewritten under stage lights. Those nights didn’t feel like memories then. They felt like the start of a fire no one had yet named.

The theater was sanctuary and mirror both. Outside, students marched, bands wailed from garage doors, joints burned in the back seats of cars. Inside, we dressed in Elizabethan tights and spoke lines about power, betrayal, and madness. Somehow it felt like the same conversation.

The counterculture leaked into the Globe like fog under a door. Hair was longer. Beads appeared at throats. A stagehand passed a joint behind a flat during intermission. Someone hummed Jefferson Airplane backstage. It was just life seeping in, the old and the new mixing the way paint does on a palette.

Some nights it was hard to tell if we were performing Shakespeare or channeling the streets outside.

One night I came out of rehearsal to find a line of students marching past the park with placards. The chants carried through the night air and into our stage windows. Inside, Prospero was summoning spirits. Outside, kids my age were summoning a different storm.

The extraordinary wasn’t extraordinary—it was ordinary. Spirits weren’t confined to The Tempest. They lived backstage, drifting in the sawdust, clinging to the ropes that raised and lowered our worlds. We spoke of them casually, the way you mention a draft in a room or the creak of a floorboard.

Once, during a run of The Tempest, a stage light blew mid-scene. A flash, a shower of sparks, darkness. The audience gasped. Will raised his staff and kept speaking. Nobody moved to fix it until the scene was done. Later, we swore the spirit had answered his call.

Backstage was another kind of stage. Costumes hung on racks like ghosts waiting to be filled. Actors prowled the narrow hallways muttering lines, half-possessed. Makeup tables glowed under hot bulbs, powders and greasepaint scattered like battlefield dust.

Between shows we sprawled in the grass outside, the smell of reefer drifting through rehearsals. Nobody pretended theater was separate from the world. It was the world, bent and refracted. Lines about kings and tyrants became lines about Johnson. Betrayals in Verona became betrayals in Washington.

The extraordinary and the ordinary lay side by side. Protesters outside with signs. Prospero inside with a staff. Spirits summoned by actors and by crowds. The line between them was as thin as stage smoke.

This was theater in 1966: part rebellion, part ritual, part circus. All the same thing.

Will didn’t just play Prospero and Friar Laurence—he was Prospero and Friar Laurence combined. Like my mother, he always planted a garden wherever he was. He planted one behind the Globe, and you’d come into the theater in the morning to find him in costume, busily pruning and tending.

His rented home at the beach was more commune than house. Stray actors, musicians, wanderers drifted in and out. They ate at his table, slept on his couches, and never contributed anything but their presence. Nobody asked where you came from. If you were hungry, you were fed. If you were homeless, you stayed until you weren’t.

He and his wife took me in that summer, like family. Their son Thad became my closest friend. We were about the same age, restless, eager for something bigger than ourselves. We surfed together when the schedule gave us a morning free. Pacific cold enough to shock you clean. Salt water, laughter, the hard burn of paddling out—it felt as necessary as rehearsal.

At night we returned to the Globe, where Will shifted from the warmth of a father at the table to the weight of a shaman on stage. When he raised his staff as Prospero, I felt like he was conjuring not just spirits, but all of us. We were his spirits. His family.

Jon was different. Younger, sharp-edged, tall enough to tower over everyone else. He carried a discipline rare for our generation. While some of us floated through rehearsals, Jon worked. He cut his lines like stone, clear and exact.

We became friends. He wasn’t flashy about it—just steady. Offstage, we’d laugh about the absurdity of playing Elizabethans in the middle of a California Navy town.

Jon didn’t surf—too tall, too lean, awkward with the board—but he stood on the sand and watched, cheering when one of us caught a clean ride.

He was serious in a way that made me listen. He told me about New York. The Neighborhood Playhouse. His mentor Sandy Meisner and his “reality of doing.” He spoke like it wasn’t a choice—if you wanted to be an actor, that was where you went.

His words planted themselves in me. San Diego, for all its magic, began to feel like an interlude. New York was coming, inevitable as tidewater.

And in the middle of it all, Will’s house remained a place where the ordinary and extraordinary met without conflict. Dinner was beans, cornbread, a guitar passed around the table. Spirits were always welcome. Nobody blinked when the wind outside rose like a chorus, or when someone swore they saw a figure move through the garden at night.

For me, by extension, it was all the same thing.

Jon contacted Sandy Meisner and I got accepted at the Neighborhood Playhouse. I was following my dream. It was all falling into place.

On my last morning in California I paddled out past the break, the Pacific rolling heavy under me. The sky was wide and merciless. My arms burned, salt stung my eyes, but I kept pushing. For one wave, I stood and rode it all the way in. Spray on my face, the roar in my ears. It felt like the ocean itself was bowing me offstage. When I turned back, the sea leaned toward me like an old friend, whispering goodbye. I believed it. I had always believed water had a voice.

Manhattan hit me like a fist. The stink of hot asphalt. Steam rising from subway grates. Horns blaring in six directions at once. Neon flickering even in daylight. The sidewalks never empty, never still.

My first nights were in Jon’s apartment while he was out of town for a month. I ate cheap Chinese food out of cartons and walked the streets wide-eyed, taking in the bustle of the Big Apple. I took big bites.

The Neighborhood Playhouse sat on East 54th, plain on the outside, a simple brick building that held another reality for me.

The school wasn’t about appearances. You showed up, you worked, and you didn’t pretend. Classes started early and ran until you were wrung out. Nobody called themselves an actor—you were a student until someone better than you said otherwise. The teachers didn’t flatter and they didn’t explain twice. You were expected to be off-book, on time, awake. If you missed a beat, you heard about it in front of everybody.

They taught with the attitude that the craft was bigger than anyone in the room. You learned to listen before speaking and to drop whatever you thought acting was supposed to look like.

Martha Graham came through sometimes. She didn’t announce herself or hold court. She might step quietly into a movement class, watch for ten minutes, say nothing, and leave. That was enough. Her presence reminded everyone that the work had a lineage, and if you weren’t ready to meet the standard, someone else was.

Nobody cared where you were from—only how you worked. You didn’t audition for attention. You earned the right to stay in the room. That was the education.

Pearl Lang had danced with Martha Graham and later ran her own company. She wasn’t a visiting name; she was part of the lineage itself, one of the people who helped define modern dance. Matt Mattox came from Jack Cole’s school of jazz—sharp lines, clarity, precision. He’d danced in films and on Broadway, but at the Playhouse he was there to train bodies, not build egos.

Pearl taught like the body was an instrument you either respected or didn’t deserve to use. She didn’t raise her voice, but she could stop a room cold with one correction. Movement wasn’t decoration—it was intention. Matt’s classes were exact to the bone. No slouching, no half-speed. You kept up, or you stepped out.

Sanford Meisner was one of the original members of the Group Theatre alongside Lee Strasberg, Stella Adler, Harold Clurman, and Elia Kazan. He’d started as an actor in New York and Hollywood before shifting into teaching. His Meisner Technique—repetition, listening, truthful reaction—became one of the pillars of American actor training.

By the time I arrived, he wasn’t in every room, but his fingerprints were everywhere. The repetition drills, the focus on impulse, the demand for honesty—you felt it in how scenes were run and how teachers corrected you. You didn’t perform emotion; you pursued action. You didn’t chase laughs or tears; you told the truth and let whatever happened be enough.

I was lucky. Many of my classes were with him directly. Even if you never worked with him, you were learning in his house, and everyone knew it.

Sandy was blunt as a hammer. His eyes burned through pretense. He didn’t want performance. He wanted truthful, spontaneous reaction under the given imaginary circumstance. Nothing less.

“The reality of doing,” he said, over and over, until the words etched themselves into your being.

Repetition drills: one student says, “You’re wearing a red shirt.” The other repeats it. Back and forth until the artifice cracks and the truth shows itself—the frustration, the joy, the hunger underneath. Acting wasn’t pretending. It was being.

One day we did an exercise where I played a commando dragging a body from another classroom. I was so absorbed I dragged it straight into a class Sandy was teaching.

“Drag that body out of here before you’re caught.”

When I left, he told his class, “Now that’s what full absorption looks like.”

Praise from Sandy was rare. If you got it, you lived off it. It was an aphrodisiac for the girls. Paula—the wet dream of every guy in school—started coming on to me after that. The sad truth was I was so shy she practically had to get me drunk to seduce me.

Dance classes under Pearl Lang were their own kind of baptism. The floorboards trembled under her sharp commands. Breath pulled through every movement until it felt like the earth itself had entered your body. Voice classes stretched sound out of your throat until it hurt, then broke, then soared.

When Jon came back to the city, I left his place and moved to Greenpoint, Brooklyn. A classmate, Ken Burns, needed a roommate. We found an apartment with cockroaches that owned the kitchen. At night the radiator clanged like a steel drum. Drafts cut through the windows like knives. I slept in socks and two sweaters. Rent ate everything.

We lived in the shadow of legends. Steve McQueen, Joanne Woodward, Gregory Peck—they had all walked through the Playhouse before us. Their ghosts haunted the hallways.

Bravado covered hunger. Everyone believed they were destined for greatness. Nobody admitted the odds.

Diane Keaton was there then too—sharp, electric, already rising toward something larger. I had a quiet crush on her, but she felt galaxies away from where I stood.

Nights stretched late in cheap cafés where we argued about art, theater, politics. We smoked too much weed, drank cheap wine and strong coffee, and dissected the world like it was ours to rebuild.

The city itself joined in. Subway tunnels throbbed like veins. The streets whispered like a restless beast. I felt tested at every corner, as if Manhattan needed to know if I could survive it.

Survival meant odd jobs: sweeping floors, waiting tables, hustling for tips. Carrying plates, folding chairs, doing anything that bought another week’s rent.

The truth was I was broke most of the time, though never starving. My diet was pizza and junk food. But none of it mattered, because I was alive. San Diego had been magic—but New York was realism. A dream turning into a life.

The Village softened the edges of everything. After the discipline and fever of the Playhouse, St. Barnabas House was another kind of stage—its audience the sleepless and the forgotten. The nights there moved slower, the air heavy with disinfectant and crayons, the muffled hum of the city outside the barred windows. That’s where I met Mary. She was steady where I drifted, careful where I improvised. Between night shifts, whispered conversations, and shared toast at a children’s table, a quiet love began—less a performance than a surrender to something real.

St. Barnabas House on Mulberry Street in the Village was a children's shelter that housed abandoned and neglected kids, though most were asleep by the time my shift began. I was the night watchman, working for room and board. The place had its own kind of silence—the shuffle of small feet, a door creaking somewhere down the hall, the hum of pipes that never quite stopped. The smell of milk, disinfectant, and the faint sweetness of crayons hung in the air like something permanent.

That's where I met Mary. She was a junior sociology major from Michigan, doing her work-study at the shelter. She carried herself with quiet assurance—organized, on time, no wasted words. Where my energy scattered like sparks, hers gathered and focused.

The first spark came during my nightly rounds. I'd stop at her room, pretending it was part of the job. We'd talk—about politics, the war, the kids, the state of the world as if we were its exhausted caretakers. One night she passed me a cigarette, and I offered her a joint in return. She hesitated, then smiled. We smoked by the open window, watching the streetlights flicker on the wet pavement below.

We didn't call it anything. It was easier to pretend it was convenience—two people in the same building, awake when the rest of the place was asleep. But something in her steadiness drew me. She asked about rehearsals like it mattered, listened when I talked about Meisner's classes, about the way truth could be stripped bare in performance. 'That's not so different from what I study,' she said once. 'We both look for what's real—only in different languages.'

After my rounds we'd sit in the kitchen, eating toast off paper napkins at a metal table meant for children. The fluorescent light hummed above us, soft and cold. She'd talk about home—snow on the lake, her mother's voice calling her in from the yard—and I'd picture it as if I'd been there.

Eventually I stopped going back to my own room. I'd finish the rounds and end up in her bed without either of us calling it a change. Some nights we talked until one of us drifted off. Other nights silence did the talking. Sharing a bed didn't make things clearer, only closer.

I still woke before dawn for class or a shift, and she still stacked her books in neat piles by the bed. We didn't name it. The shelter wasn't a place for declarations. You just went on until something made you stop.

Being with Mary didn't cancel the rest of my life, but it softened it. The noise of the city, the pressure of ambition, even the ghosts of the stage—all of it quieted when she was near. I told myself it was company, but I knew better. I was choosing her, and she was choosing me, quietly, without promise.

When summer came, Mary went home to Michigan and I went south to Alabama to stay with my cousin Bill. The air there was heavy and still, the nights long. I lay awake replaying her laugh, the way she listened, the calm that settled over me when she spoke. The distance felt physical, like gravity pulling the wrong way.

I didn't know it then, but something had already taken root—just as real as the roles I chased or the dreams that sent me east. I thought I had left New York behind for a while. I didn't understand that part of me had stayed with her. And that was how the next chapter began—quietly, with distance, longing, and the first outline of a life I didn't yet see coming.

Not long after I came east, I got the call that changed everything: Mary was pregnant. The world tilted. The noise of New York blurred into a single, quiet certainty—I was going to be a father.

We were married quietly. No grand audience, no spotlight, just my Uncle Jimmy and her family, vows exchanged under the weight of something bigger than either of us had expected. There were rings, a few witnesses, and the sound of our own voices promising something we didn’t yet know how to live.

Mary was steady, determined. She believed in building a life, in family, in me—even when she must have already seen the chaos flickering just beneath my skin. I didn’t know how to deserve that kind of faith.

We moved back to Victorville, where the Air Force base still cast its long shadow over the desert. The town hadn’t changed much since I’d left—just the same windblown motels, the same gas stations humming under the heat. We rented a small stucco place with cracked linoleum floors and one good window that looked west toward the Mojave. It was barely enough for two, and yet we began preparing for three. Then came the news. Twins.

I remember one afternoon when the desert light slanted through the blinds and caught her just right. She was sitting on the edge of the bed, one hand resting on the swell of her huge stomach as if holding something fragile from the inside. She was calm in a way I was not. She took my hand and placed it on her belly, and for a moment the world stopped its noise. One of the babies kicked—sharp, certain—and she smiled without looking at me, as if the child and she were sharing a private joke I had not yet earned the right to hear.

In that moment she looked ancient and impossibly young all at once. Like a fourteen-year-old girl pretending at motherhood, and like a mother who had already lived a thousand lives.

Before they were born, I imagined fatherhood as a role I could rehearse my way into. I pictured myself holding a baby in one arm while reading a script in the other, charming and unshaken, stepping in and out of responsibility the way I stepped on and off a stage. But the real thing didn’t wait for my cues.

It was two babies crying at once, nights that bled into mornings without applause or intermission. There were moments I stood in the hallway holding one child while the other wailed in the next room, and I knew—without a doubt—that the life I had pictured was a fantasy, and the one I was standing in belonged to men much steadier than me.

Mary was my anchor. She carried the weight of everything—feedings, exhaustion, a home that felt too small for so much life—and she did it without complaint. I enrolled full-time at the college, took leads in the school’s productions, and told myself I was building a future for all of us. But the truth was, Mary was the one doing the building while I was still chasing the light.

I remember one night after rehearsal, standing outside our little house under the desert stars. The air was so dry it seemed to hum. Through the window I could see her rocking one of the twins, the other already asleep. The blue light from the television flickered across her face. She looked peaceful and alone. I stood there for a long time before I went inside.

By the time the next season came, I had made my decision. I would return to the Old Globe. Mary didn’t protest. She just nodded, eyes steady. 'You have to do what you’re called to do,' she said. But I heard what she didn’t say. And that silence stayed with me longer than any applause ever would.

San Diego glittered like a mirage—sunlight, surf, and a growing darkness behind the laughter. Theater and counterculture blurred until there was no line between rehearsal and ritual, role and reality. The Old Globe was still my temple, but the prophets had changed. LSD replaced prayer, and the stage lights burned hotter than conscience. What began as curiosity became momentum. Love went north. Madness stayed.

The heat from the stage lights made every costume feel like armor. Sweat, makeup, adrenaline—it was theater as confession. When the curtain dropped, we didn’t come down; we just changed scenes. The line between stage and life was gone, and none of us wanted it back.

Marco St. John was there, bigger than life, full of the kind of swagger that made him unforgettable both onstage and off. A classically trained actor at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London, Marco was a southerner, brash and magnetic, and lived like every day was an opening-night party—and somehow he always got away with it.

Then there was our stage manager, who became my best friend: Richey Mensoff. I met him my first day, sitting backstage in buckskin jeans, smoking a joint. I cautioned him that I’d heard the stage manager was around. He just smiled. “I am the stage manager.”

Marco roared through rooms like he owned the air. Richey balanced him—quiet eyes, dry humor, always fixing what others broke. Together they were a living metaphor for theater itself: chaos and control trying to share the same cue.

I had one foot in discipline and another in appetite. Between them, I learned that theater was both a religion and a circus, sometimes in the same scene. I was twenty, already a father of twins, when the madness started to creep in. The stage no longer satisfied the hunger. Something else called, something darker.

Enter Richard the Warlock.

An old beatnik turned hippie who had fashioned himself into a guru. He ran the first head shop in Pacific Beach, a storefront that smelled of incense and hash, glass cases gleaming with pipes and papers. His shop smelled of sandalwood and revolution. Posters glowed under black light—Hendrix, Dylan, the moon landing beside a sign that read Turn On, Tune In, Drop By.

He wasn’t quiet. He spoke fast, sometimes in a whisper, flashing a grin that was more devil than saint. It was a performance, and it worked like a charm, sweetened with the weed and LSD he dispensed like candy. Young women orbited him, with names he gave them like Psychedelic Nancy or Sweet Sue—devotees to his guru act. He spun half-truths and cosmic promises, and they nodded as if he were Moses himself.

I knew it was manipulation. But I didn’t walk away. I became a smuggler.

Richard showed up at the Globe one night to see Hamlet, drifting in with Psychedelic Nancy on his arm like he owned a different kind of theater altogether. She was barefoot in a paisley dress that floated when she walked, pupils blown wide before the lights even dimmed.

He watched the play like it was being performed only for him, head tilted, smiling at lines no one else laughed at. After the show he slipped backstage, moving past actors and crew as if he had always belonged there. He didn’t ask—he announced that we were all going back to Marco and Barbara’s.

By the time we got to their place, Richard had taken command without raising his voice. He opened his satchel like it was a magician’s kit—tabs, capsules, a vial or two—and everyone gravitated to him the way drunks move toward music. Nancy curled up on the floor and stared at the ceiling like constellations were rearranging themselves just for her. Marco and Barbara didn’t host that night; Richard did.

He passed out the doses like communion, speaking in half-prophecies and jokes only he understood. I told myself I was just along for the ride, but the truth was I followed him the way I followed good actors—I wanted to see how far he would take the scene.

Nancy floated over to where I was sitting on the arm of the couch, moving like she didn’t quite believe in gravity. She lowered herself onto the floor at my feet and rested her chin on her knees, staring up at me like she was waiting for a line I hadn’t rehearsed. Her eyes were all pupil and wonder.

“You ever look at your hands on acid?” she asked, like it was the start of a religious text. Before I could answer, she took mine and turned it over in hers, studying my palm as if she were reading a script written under the skin.

“You have traveler lines,” she said, tracing them with one finger. “You’re not gonna stay where you are. People like you break things to see what’s inside.”

Richard overheard and laughed from across the room, said she was right, that I was already halfway gone and too stoned to notice. Everyone laughed with him. I did too, like it was a joke. But Nancy didn’t. She just kept holding my hand like she knew exactly where the night would end and how far it would take me.

Five hundred kilos a run. Packed tight, sealed, hidden. Enough to stone the entire fleet in San Diego for a day. That was the scale. That was the madness. And I stepped in—actor doing a role as a smuggler.

Mary and the twins went back to Michigan to stay with her mother. She hid her fear. I was blind to it. I had only the madness.

The load came at night. Don and I met Richard at his storeroom. The weed was pressed into kilo bricks, wrapped tight in plastic and tape. Heavy blocks, built for transport. We rented a moving van and piled boxes of clothes, cookware, and books bought cheap at thrift stores on top of the cargo. We drove straight through. One at the wheel, one asleep. Coffee for the driver. Joints and downers for the sleeper.

Somewhere in Arizona, dawn broke pale and merciless. I looked over at Don asleep in the passenger seat, his mouth half-open, and for the first time it hit me—if we were caught, everything was over. But the thought dissolved as fast as it came. The engine hummed like a mantra. The road pulled us forward.

We stopped only to eat. At a checkpoint we bought coffees and handed them to the patrol on the far side. They waved us on. We were invincible and invisible. The magic moved us forward and shielded us. No fear.

At night the road turned liquid. Headlights from oncoming cars stretched and bled across the windshield like paint dragged by a brush. The yellow lines on the highway pulsed and twisted, sometimes floating up and curling back toward us like ribbons. Don and I passed a joint back and forth without looking at each other, our hands moving on instinct. The hum of the tires sounded like chanting—low, rhythmic, hypnotic.

There were moments when I was sure we were gliding above the asphalt, not touching it at all, the van weightless and charmed. Every shadow on the shoulder looked like a figure watching us pass. I wasn’t afraid. I thought the universe had cleared the road just for us.

In New York the drop was fast. Ron Gold, a Globe actor and friend, had the connections. Money shifted hands. The bricks disappeared. The city swallowed them whole.

Money didn’t quiet the hunger. It only fed it. I told myself it was freedom, but it was just velocity—the kind that blurs everything you love in the rearview mirror.

Now I had money to fuel my madness.

I took an apartment in Marco and Barbara’s building at 77 Perry. Richey Mensoff lived there too. A vertical tribe stacked on top of itself. The madness followed me, this time with money to feed it.

The Village pulsed. You could leave a midnight set at the Fillmore and still make last call at Max’s. Hamburgers up front, speed and smoke in the back. Factory kids floated through like silver-painted ghosts. Marco moved among them as if born under a spotlight. Andy Warhol observed the room like a cat watching a fishbowl—silent, amused, noticing everything.

Through Marco and Barbara I met Viva, one of Warhol’s superstars. Sharp, strange, beautiful in a way that made you think she already knew your ending. She had a philosopher’s nerve and a comedian’s timing. Everyone in Warhol’s orbit seemed to live on tape—every glance and stumble a possible scene for his next film.

One night I ended up at Bob Richardson’s loft, the fashion photographer who’d exploded out of Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue. His photos looked like confessions captured through smoke—blurred, erotic, dangerous. He was part prophet, part burnout. Norma, his wife and muse, radiated the same haunted beauty from his prints.

The three of us dropped acid and the night unfolded in slow motion. Curtains breathed. Walls shimmered. We drifted between words, laughter, and touch—intimate but tender, like trespassing at the edge of revelation.

When I finally returned to Perry Street, still buzzing, Viva was waiting. She looked once and asked, “Where have you been?” like she already knew. I started describing the night before she even asked. She listened without interrupting, head tilted, pulling the thread. Later I learned she was writing Superstar—and she recorded my story, turning my LSD confession into something that sounded like poetry instead of evidence.

The Living Theatre was its own universe—part sanctuary, part battleground, part commune. Julian Beck and Judith Malina had created a company that treated theater as a form of civil disobedience, where art wasn’t something you watched but something that collided with you. Their shows stripped away sets, costumes, hierarchy—anything that separated performer from witness. They believed the stage was a place to unlearn obedience, to expose the violence of society by refusing to mimic its rules. Walking into their world felt like stepping into a rehearsal for revolution, one where the script changed nightly because the real point was liberation.

Backstage at the Living Theatre felt less like a green room and more like a war room for a revolution disguised as art. Julian Beck and Judith Malina believed performance could dismantle power—that bodies could break laws just by refusing to be afraid. Paradise Now wasn’t a play; it was prophecy.

Richey and I sat cross-legged with three cast members, a box of Zig-Zags dumped like confetti, and a mountain of grass. Someone said the audience needed three hundred joints—equal parts communion and ignition—so we rolled. Smoke pooled under the catwalks. Actors drifted by naked or half-painted, whispering lines that sounded like prayers or warnings. Rolling joints there felt like building a set or writing a manifesto.

After the show, Julian and Judith led a small group of us to Ratner’s on Second Avenue. The restaurant was nearly empty, the kind of quiet that follows something unruly. Judith smiled across the booth, eyes still bright with stage fire. Julian spoke like a poet-conspirator, vibrating from the ritual they had just unleashed. They talked about theater as a weapon, the sacredness of breaking boundaries. Judith leaned forward like she was recruiting me without ever saying it. I didn’t know whether I was cast, converted, or simply passing through. I only knew I didn’t want to be anywhere else.

Mary and the twins finally joined me. We moved to Staten Island because that’s what families did—commute by ferry into Manhattan like adults with briefcases. I told myself it was a bridge between worlds.

The building was an old Irish pub with a tight two-bedroom above it. The apartment stayed the same. The bar downstairs, I gutted. I ripped out taps, rails, stools—everything that smelled like last call. What had been a pub became a loft with beanbag chairs where tables once stood and clothing racks along the walls. I turned the basement into a work zone—sorting, packing, cutting, whatever the next idea demanded. I paid cash for the entire building. It wasn’t a home; it was a staging ground. But Mary made it livable, and I pretended that counted.

The business took off. Mademoiselle and Glamour called. Editors came to my loft-showroom and told me the next trend. I learned how to sell without sounding like I was selling—let them touch the cloth, keep the pitch short, leave one thing they couldn’t have yet.

GlobalMart smelled opportunity. They offered to buy forty-nine percent with fresh IPO money. With my signature, I could buy a quarter-million dollars’ worth of goods anywhere in the world. Their marketing budget could run an entire campaign. We celebrated the way young people with money do—loud, constant, without brakes.

Then the establishment locked the door. NAMSB froze us out of the big show at the Hotel McAlpin—too brash, too new, too young. So we rented a loft across the street and turned three empty floors into a guerrilla showroom in seventy-two hours. Banners in the windows. Actor friends registered as buyers, dressed head-to-heel in the vest suits I cut for them—cheekbones sharp, hair too long for the old guard.

Security tried to toss us the minute they realized the game, but the buyers rallied. The old guard crossed the street out of curiosity and stayed out of hunger for whatever was happening. We sold out the first run on day one.

They called it guerrilla marketing. I called it opening night.

I was twenty-three and told anyone who asked that I’d be a millionaire before twenty-five. It didn’t feel like bragging. It felt like weather.

Then came the call from South America. Old friends. A whisper from a government office. Otavalo artisans needed new work; the poncho fad had died. Embroidery on new silhouettes. The idea cut through my haze like a bell. Ecuador. The mountains. The plaza that taught me to listen with my eyes. I said yes before the sentence finished. The designs were already in my head.

In Quito, life found a rhythm. Mornings of fruit, bread, black coffee, sometimes a line or two to clear the fog. Then to the cut-and-sew shop. We dyed rough cotton in ice-cream colors and sent pockets and yokes to Peguche, where Otavalo women embroidered them by hand. Lunches of beer or chicha. Evenings in bars, clubs, hotel terraces. Some nights the Peace Corps doctor and I ended up at the Hotel Quito casino, gambling on acid, dancing when we won. Nobody cared. I made too much money. I was interesting. Even the embassy people laughed it off.

In Peguche, I was a guest. The women worked slowly, quietly, as if time had to earn their trust. Designs bloomed under their fingers—birds, suns, lightning. Each unique. Men dyed threads in tubs steaming under the mountain sun. Earth, woodsmoke, wet cotton perfumed the air.

I named the trade lines Sundance and Inca Terra. They sold before they shipped. Buyers loved the story—indigenous craft with modern cut. But what I loved was the process. The rhythm. The color. The mountains turning silver at sunset.

For the first time in years, I felt something close to peace. It didn’t last.

Ecuador shimmered between vision and illusion. In the thin air of the Andes, success began to sound like prophecy, and dreams spoke louder than reason. Mama Rosa warned that the wind had shifted, but I mistook her wisdom for poetry. What followed was written in the same invisible ink as the dream itself—its meaning clear only in hindsight.

I set up production in Ecuador. My trade names were Sundance and Inca Terra. We embroidered western-style shirts and jean pockets. Mama Rosa, the matriarch of Otavalo, became my Indian mother. She organized the women who did the embroidery, and together they set trends that still echo in markets today. I paid cash for everything. The work, the materials, the silence.